How Multibaggers Really Happen

The Data and Research Behind Extreme Stock Market Winners

Every investor dreams of a multibagger, a stock that turns into a 5×, 10×, or even 100× return. These stories dominate investing books, podcasts, and X threads.

But when you step away from anecdotes and look at decades of market data, the facts are clear:

Multibaggers are statistical outliers that live in the extreme right tail of returns.

That changes how they should be approached. Instead of chasing tips, hype cycles, or the latest narrative, the smarter path is to learn from research and data.

Academic studies don’t give us a guaranteed formula for finding the next Nvidia or Amazon, but they do tell us which kinds of companies are far more likely to produce extreme winners, and which almost never do.

Investing is not about certainty. It’s about tilting the odds in your favor.

The Majority of Stocks have Negative Returns

One of the most robust and yet misunderstood facts in investing is just how unequal stock returns really are. Hendrik Bessembinder’s wealth-creation research puts hard numbers on this inequality. From 1926 to 2019, U.S. equities generated $47.4 trillion in net shareholder wealth relative to Treasury bills, but almost all of it came from a tiny minority of companies.

Out of roughly 26,000 listed firms, just 83 stocks accounted for half of all wealth created. Narrow it further, and the concentration becomes even more striking. Only five companies, Apple, Microsoft, Exxon, Amazon, and Alphabet, generated nearly 12 percent of total U.S. stock-market wealth over the entire 94-year period.

This concentration is not shrinking. By 2019, the top two stocks alone explained 6.45 percent of all wealth created since 1926, and the top five explained 11.9 percent, up from about 10 percent just three years earlier. Long-run market wealth is not built by the average company. It is built by a handful of extreme winners that dominate everything else.

The median stock experience looks nothing like the success stories investors remember. Using data on nearly 30,000 stocks, Bessembinder shows in a recent paper that about 52 percent delivered negative lifetime returns. The typical stock destroyed capital over its entire existence.

At the same time, the upside is extremely concentrated. Just 17 stocks turned one dollar into more than $50,000. The single best performer compounded one dollar into more than $2.6 million. Out of nearly thirty thousand stocks, fewer than two dozen explain a staggering share of all long-term wealth creation.

Real examples make this tangible. Altria turned one dollar into well over $2 million. Nvidia delivered the highest sustained annualized return ever recorded for a stock with at least twenty years of history, roughly 33 percent per year, long before it became an AI darling. Apple created about $1.6 trillion in shareholder wealth since the early 1980s, while Amazon turned repeated crises into nearly $900 billion of wealth creation.

What makes these outcomes even more counterintuitive is how they were achieved. The greatest stocks in history did not rely on extreme annual returns. Across the top performers, long-run returns averaged only the low-to-mid teens, and even the very best rarely sustained more than 30 percent per year. What separated them was not dramatic short-term growth, but survival, reinvestment, and time.

This is the tension investors underestimate. Long-term equity wealth is very real, but it is created by a vanishingly small subset of companies that rarely look exceptional when long-term outcomes are decided.

What the Data Says You Should Actually Look For

Anna Yartseva’s recent paper, The Alchemy of Multibagger Stocks, moves beyond distributional facts and asks the question:

Do multibaggers share identifiable traits?

She studies 464 U.S. stocks that increased at least tenfold between 2009 and 2024 and estimates models that combine size, valuation, profitability, price behavior, and macro variables. The sample excludes stocks that briefly became multibaggers and then reversed, focusing only on those that sustained their outperformance.

Because the analysis begins in early 2009, just after a historic market collapse, the results describe what separates long-term winners among crisis survivors. That makes them especially relevant for understanding how multibaggers emerge out of periods of stress, when valuations are low, and expectations are depressed, even if the dynamics may differ in late-cycle or speculative environments.

Some classic intuitions survive. Multibaggers tend to be smaller, cheaper, and more profitable than the average stock. These are not glamorous mega-caps. They are economically viable small-cap firms whose long-term potential has not yet been fully priced.

Free cash flow is particularly important. In Yartseva’s models, cash generation is the strongest predictor of outperformance. Multibaggers are not built on narratives. They are built on businesses that can fund their own growth.

Moreover, the paper finds that momentum behaves very differently for multibaggers than most investors expect. Multibagger stocks load negatively on both 3-month and 6-month momentum, and stocks trading close to their 12-month highs tend to underperform. In fact, Yartseva finds that the best entry points are typically when prices are near their 12-month lows after a significant prior decline, reflecting rapid trend reversals rather than smooth momentum. Often, the best entry points for future giants don’t look like typical breakouts at all.

Their price paths are typically choppy, full of reversals and long consolidations, reflecting a gap between improving fundamentals and skeptical markets. That is precisely why these stocks are so difficult to own before their compounding becomes obvious.

Looking at the multibaggers’ starting point in 2009 makes this concrete. Adjusted for inflation, the median multibagger began as roughly a $500 million company in today’s dollars. Median revenue growth ran in the low double digits, return on equity sat in the high single digits, and valuations were modest, with forward P/E ratios in the low teens, price-to-book near one, price-to-sales around 0.5, and PEG ratios below one.

These were not moonshots or narrative favorites. They started as small, financially sound, conservatively valued businesses whose long-term potential was underestimated.

What to Avoid Matters Just as Much

Knowing what to avoid is often more important than knowing what to buy, and Yartseva’s results are just as revealing on the downside.

Pure growth stories without cash generation rarely become multibaggers. Companies that cannot fund their expansion from operating cash flow tend to deliver much weaker outcomes. Likewise, large, widely owned stocks struggle to deliver extreme outcomes because most of their future success is already priced in.

Asset growth adds a critical nuance. Multibaggers do invest aggressively, but only when that investment is supported by operating performance. Yartseva finds that when asset growth outpaces EBITDA growth, next-year returns fall by roughly 23 percentage points on average. Growth itself is not the problem. Unfunded growth is.

Bessembinder’s research adds an important final warning. The stocks that become extreme losers tend to start out extremely volatile and speculative. In contrast, multibaggers usually begin as economically viable businesses rather than lottery tickets. Extreme volatility may look exciting, but over the long run, it is far more closely associated with blow-ups than with compounding.

Which Industries Produce Multibaggers?

A common belief is that multibaggers are only a technology phenomenon. Yartseva’s evidence from 2009 to 2024 paints a broader picture. Extreme winners appear across many industries. Technology is important, but it does not dominate. Healthcare, industrials, and consumer businesses all contribute a large share of the multibagger population.

Bessembinder’s long-run data, stretching back to 1950, reinforces this from a different angle. Technology has produced some of the biggest individual winners, but it has also produced an unusually large share of extreme disappointments. In contrast, sectors such as healthcare, energy, and telecommunications account for a disproportionately large share of long-term value creation.

The sectors that produce multibaggers shift over time, but the underlying pattern is stable. Extreme winners emerge in industries that allow for a wide dispersion of outcomes, where many firms fail, but a few can scale and compound for decades. Multibaggers do not require fashionable industries.

Prepare For Drawdowns

Even the greatest winners are brutal to hold.

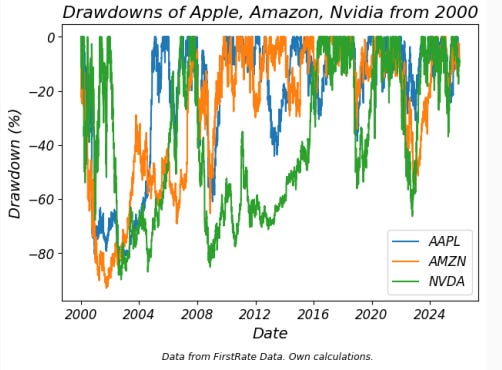

Bessembinder shows that among the 100 most successful stock-decade outcomes, the average drawdown during the winning decade exceeded 30%. In the decade before the breakout, it exceeded 50%. Many of history’s best investments looked broken on the charts long before their compounding began.

The real-world paths match the statistics. Apple endured repeated 60–70% drawdowns on its way to becoming a generational compounder. Amazon fell nearly 90% during the dot-com bust and still became one of the greatest wealth creators in history. Even Nvidia, now viewed as a model of sustained growth, suffered multiple 70–80% crashes before its long-term compounding became obvious.

Multibaggers are volatile because uncertainty persists far longer than investors expect. That volatility is not a flaw; it is what prevents easy early ownership and allows extraordinary compounding to occur. Most investors do not miss multibaggers because they fail to identify them. They miss them because they cannot stay invested through the drawdowns.

Multibaggers reward patience and conviction, but that conviction takes different forms. Discretionary investors rely on belief in the business, management, and competitive moat. Systematic investors rely on confidence in their factor models, data, and backtests rather than in individual stocks. In both cases, the challenge is the same: Staying invested when it feels uncomfortable.

Finally, the return distribution makes one thing clear: Multibagger risk must be managed at the portfolio level. The rational way to pursue extreme upside is through disciplined position sizing, either by diversifying across companies or by using a barbell structure that pairs stable, income-producing assets with a smaller sleeve of high-risk, high-upside bets. Most positions will disappoint, but a few winners can dominate the outcome.

What This Means in Practice

The research does not give us an exact formula for finding the next Apple or Nvidia. But it does give us a powerful framework for tilting the odds toward extreme winners while avoiding the mistakes that destroy capital.

For investors who use screens or systematic models, these research papers point to a clear set of principles.

What multibaggers tend to look like

Small, but not obscure

Median starting market cap was around $500 million in today’s dollars, economically viable, but still underfollowed. Focus on micro- and small-caps, not lottery tickets.Cheap or reasonably priced

Forward P/E in the low teens, price-to-book near one, price-to-sales below 1, and PEG ratios below 1 were common starting points.Positive free cash flow is a strong predictor

These firms fund growth internally rather than excessively relying on capital markets. Cheap valuations plus real cash generation help avoid value traps.Steady, not explosive, growth

Starting points were median revenue growth in the low double digits and ROE in the high single digits. The advantage comes from compounding a solid business over time, not from chasing hypergrowth.Messy price action

Long consolidations, sharp pullbacks, and choppy trends are normal. Multibaggers rarely look like smoothly trending stocks.

What to avoid

Story-driven growth without cash flow

Businesses that must continually raise capital to survive rarely become long-term compounders.Aggressive asset growth without earnings support

When asset growth outpaces EBITDA growth, future returns collapse; it’s the classic empire-building problem.Large, widely owned stocks

Once expectations are fully priced in, the math of compounding works against you.Weak balance sheets and excessive leverage

High debt increases the risk of dilution, distress, or forced selling, all enemies of long-term compounding.Extremely volatile, speculative stocks

Extreme volatility is a hallmark of decade-long losers, not winners. Multibaggers often start as boring, improving businesses.

Possible ways to build this into a portfolio

Diversify across many candidates

Most will disappoint; a few will dominate. Diversification reduces stock-specific risk, but it does not eliminate market risk. Be prepared that during major sell-offs, correlations go to one, and much of the portfolio will move together.Use a barbell structure

Pair stable, income-producing assets with a smaller sleeve of high-risk, high-upside multibagger bets.Apply disciplined position sizing

Position sizes should reflect both the uncertainty of individual stocks and the role the multibagger sleeve plays in the overall portfolio.Design for drawdowns

Most multibaggers experience brutal drawdowns along the way. If your portfolio or your psychology cannot withstand that, capturing asymmetric returns becomes hard.

These research results provide a useful starting framework for tilting the odds toward extreme winners while avoiding some of the most common ways investors destroy capital.

But they are not the whole story. Decades of research have identified other robust drivers of long-term returns, from quality and balance-sheet strength to investor behavior, sentiment, and timing signals. Layering those signals on top of the multibagger traits outlined here can further improve the odds.

I plan to explore those additional dimensions in future posts.

References

Bessembinder, Hendrik, 2020, Extreme stock market performers, Part 1: Expect some drawdowns, SSRN Working Paper 3657604.

Bessembinder, Hendrik, 2020, Extreme stock market performers, Part 2: Do technology stocks dominate?, SSRN Working Paper 3657609.

Bessembinder, Hendrik, 2020, Wealth creation in the U.S public stock markets 1926 to 2019, SSRN Working Paper 3537838.

Bessembinder, Hendrik, 2024, Which U.S. stocks generated the highest long-term returns?, SSRN Working Paper 4897069.

Yartseva, Anna, 2025, The Alchemy of Multibagger Stocks: An empirical investigation of factors that drive outperformance in the stock market, Working Paper.

Disclaimer: This newsletter is for informational and educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. The author does not endorse or recommend any specific securities or investments. While information is gathered from sources believed to be reliable, there is no guarantee of its accuracy, completeness, or correctness.

This content does not constitute personalized financial, legal, or investment advice and may not be suitable for your individual circumstances. Investing carries risks, and past performance does not guarantee future results. The author and affiliates may hold positions in securities discussed, and these holdings may change at any time without prior notification.

The author is not affiliated with, sponsored by, or endorsed by any of the companies, organizations, or entities mentioned in this newsletter. Any references to specific companies or entities are for informational purposes only.

The brief summaries and descriptions of research papers and articles provided in this newsletter should not be considered definitive or comprehensive representations of the original works. Readers are encouraged to refer to the original sources for complete and authoritative information.

This newsletter may contain links to external websites and resources. The inclusion of these links does not imply endorsement of the content, products, services, or views expressed on these third-party sites. The author is not responsible for the accuracy, legality, or content of external sites or for that of any subsequent links. Users access these links at their own risk.

The author assumes no liability for losses or damages arising from the use of this content. By accessing, reading, or using this newsletter, you acknowledge and agree to the terms outlined in this disclaimer.

Thank you